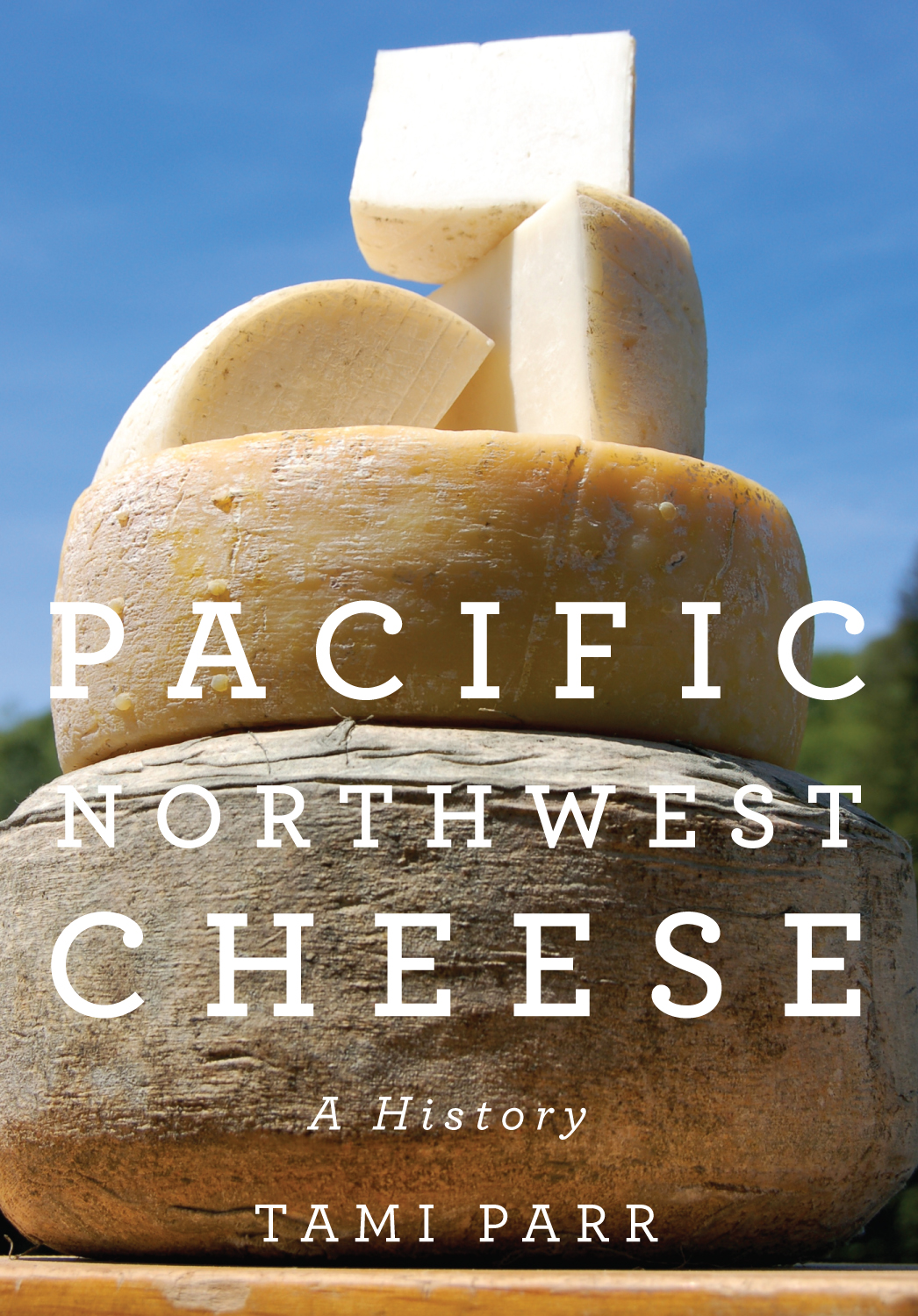

Pacific Northwest Cheese: A History

Tami Parr's new book, Pacific Northwest Cheese: A History, is a read fit for history buffs, cheese geeks, and anyone who appreciates research that connects things as seemingly distant as the onset of tuberculosis to the rise of dairy goats in Oregon. It's the type of book that would compel those who loved Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, or a reader that would seek out a 1970's copy of The World Atlas of Cheese (yup, that's me). Put it on the list for your cheesemonger friends.

Parr sets the scene with a chapter tracing pioneers's treks to the Pacific Northwest, connecting the journeys to the Lewis and Clark Expedition and government pushes to populate the resource-rich region. The first milkings begin, in fact, along the trek, when Parr notes that the rocking motion of the pioneer wagons meant hands-free churned butter. Dairy for early Pacific Northwesterners meant survival. Milk was quickly turned into butter or fermented into cheese so the milk wouldn't spoil. It wasn't until later that it became an industry.

One of my favorite parts of the book was Parr's exploration of goats. I've always found Oregon and Washington's goat cheeses to have a je ne sais quoi, a certain vivaciousness and depth to them that suggests they've been doing it for a year or hundred years longer than the rest of the country. According to Parr, this is true. The region always welcomed dairy goats, especially during the bovine tuberculosis scare, the milk flourished here during world war rationing, and the animal stayed on and thrived. Those mountains are great climbing fun for our chèvre friends, too.

Parr covers Cougar Gold (quite possibly the only tasty canned cheese in the world), the invention of rindless cheese, Oregon and Washington's attachment to blue mold, and the start of the artisan cheese back-t0-the-land movement in the area.

Though it might seem a bit dry at times for readers attached to lots of metaphors and colorful similes, Paar is a very good writer and skillfully sums up a wealth of research in a way that would make many academics jealous. And as with the butter churning bit above, she's not opposed to sprinkling her findings with the fun facts of early cheese life, such as those detailing the duties of an early cheese cooperative inspector.

"One of Christensen's first tasks," says Paar, "was reportedly weeding out the heavy drinkers among the cheesemakers and substituting sober ones- a move that no doubt had an immediate positive effect on the quality of the region's cheese."

I also like that Paar notes emerging styles and non-Euro focused cheese makers like the Ochoa Family in Oregon and doesn't shy away from talking about the colonization of the area, even as it relates to dairying.

All in all, I would highly recommend this book for those ready to dive into the deep subject of cheese or Pacific Northwest history. It, and a wedge from a modern artisan producer she discusses in her book, like Briar Rose, Juniper Grove, or Tumalo Farms, would make a caseophile very happy.